Print Page

Print Page

Print Page

Print Page

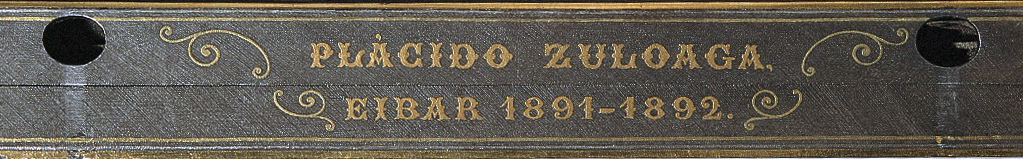

Date: 1891-1892

Location: Spain, Eibar

Dimensions: 42 x 61.5 x 37 cm

Accession Number: ZUL 109

Other Notes:

The frame of this casket is constructed of wrought iron preshaped ‘beams’ that have been carefully mitred and joined to form frames for five rectangular and four trapezoidal panels. Unlike other caskets by Plácido, the structure of this one consists of all straight lines and angles with salient mouldings; the framework ties into four squared columns which form the corners and terminate in square feet formed as broad mouldings.

The iron has been gilded and subsequently damascened in its recessed areas. The damascening, in silver and gold, is done in patterns of delicate foliage of Renaissance design. The frame supports nine panels of what appears to be silver repoussé, whose ornament is in the form of birds and grotesque animals surrounded by tendrils, foliage, and exotic flowers very much in the manner of late seventeenth-century baroque design. The background of these panels is enamelled in dark blue. To the centre of the forward panel of the base is affixed a circular bronze medallion containing a classical female bust in high relief. An iron handle chiselled in the round in baroque design is also gilded and has as its central element a grotesque satyr’s head.

This casket represents a departure from Plácido’s style, and would not be immediately attributable to him were it not signed. However, once its authorship is recognized, it is possible to perceive structural and thematic similarities between General Prim’s catafalque and the present piece, including the silver repoussé panels.

By the same token one might postulate a connection between the enamelled repoussé and the work of Plácido’s younger brother Daniel. Eusebio, their father, had sent Daniel abroad as a young boy to study enamelling, and while he would eventually make his name as a ceramist, Daniel was proficient as an enameller as well as being an accomplished designer. His baroque designs for ceramic architectural panels show a striking similarity to these panels by Plácido’s, and also to the classical medallion.

This casket must have had a special purpose since its lid lifts entirely off instead of being hinged. When the lid is raised, the signature on the forward lip of the base is revealed.

Bibliography:

J. D. Lavin (ed.), The Art and Tradition of the Zuloagas: Spanish Damascene from the Khalili Collection, Oxford 1997, cat. 19, pp.110–3.