Print Page

Print Page

Print Page

Print Page

Date: dated 1897

Location: Germany, Berlin

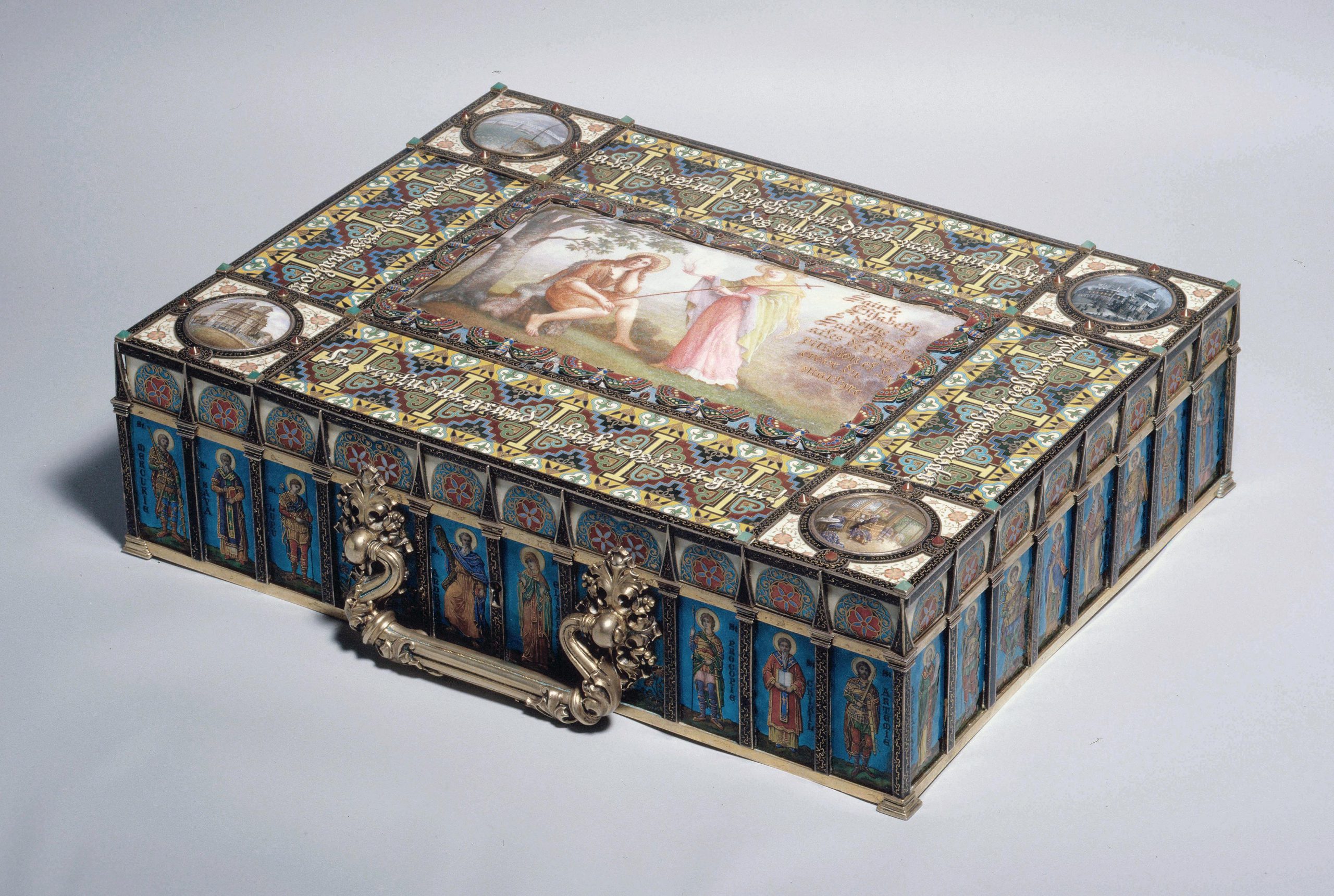

Materials: silver-gilt, opaque and translucent champlevé, painted and gilded enamel, coloured hardstones

Dimensions: 10 x 36.2 x 29 cm

Accession Number: GER 189

Other Notes:

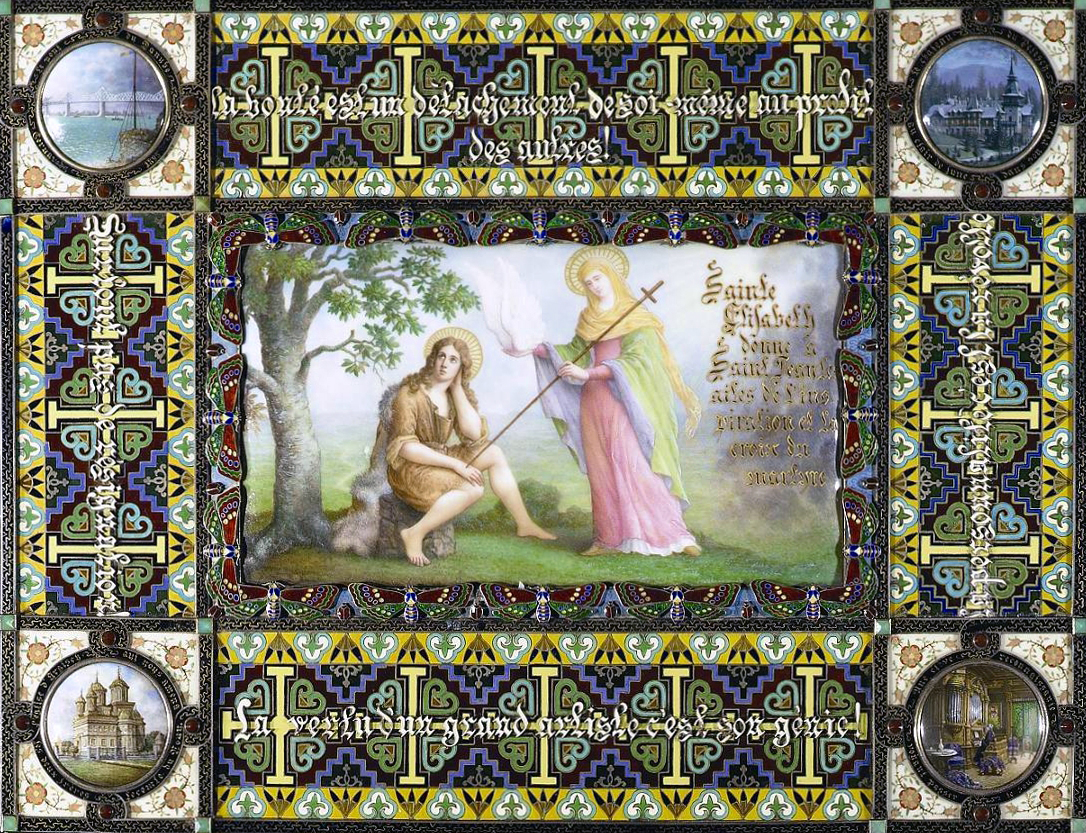

The base is inscribed ‘En souvenir des oeuvred | dont les frères André et | Jean Lecomte du Nouÿ | ont dote la Roumanie | Témoignages d’affection | et de reconnaissance éternelles | Elisabeth | Sinaïa | Oct. 1897’.

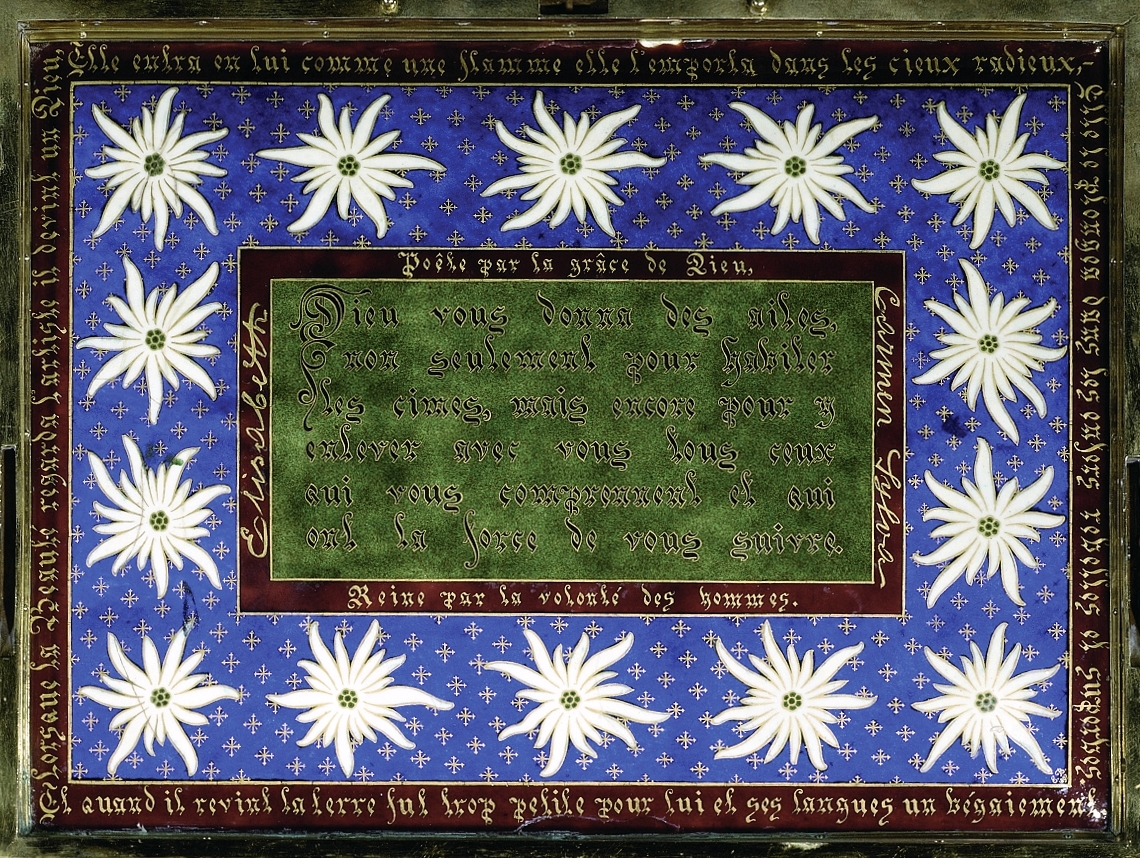

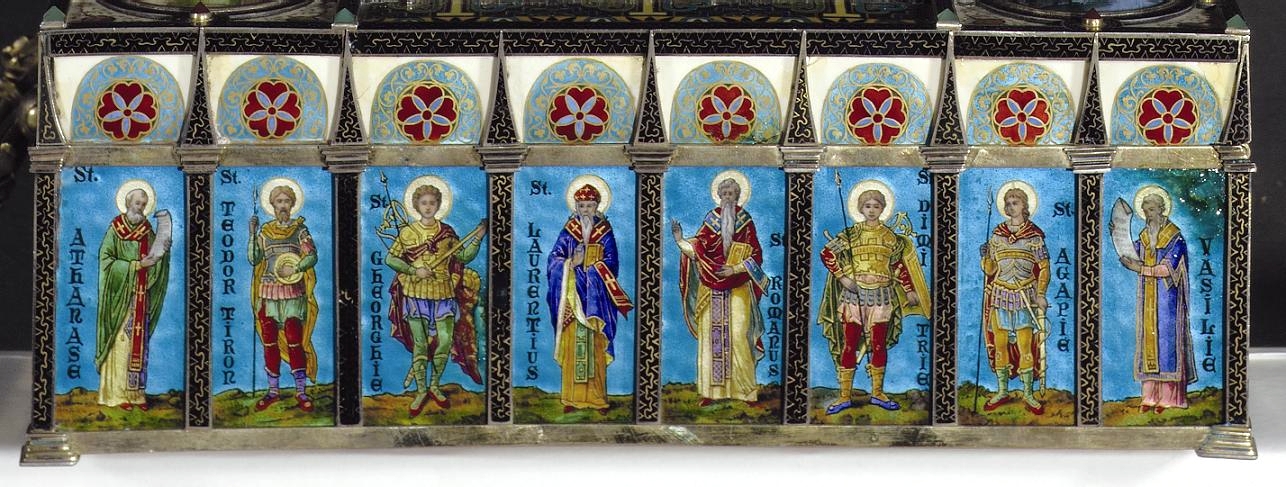

Elisabeth (1843-1916), only daughter of Hermann, 4th Prince of Wied, married in November 1869 Carol I, Prince, later King, of Roumania (1839-1914). In contrast to the pragmatic and austere king, whose efforts transformed what had been an impoverished province into a wealthy state, Queen Elisabeth was an archetypical romantic, described by her successor, Queen Marie, as ‘both splendid and absurd;. The author of many tales and poems, published under the pseudonym of ‘Carmen Sylva’, the queen sought out the company of artists, writers and musicians – not all of conspicuous talent – who formed an admiring court around her. Many of them received tokens of her esteem, including Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ (1842-1923), who was given this specially comissined casket made by the Berlin silversmith Paul Telge. The iconography, maxims and texts – dwelling on themes of creativity and genius – were suggested by the queen and signed ‘Elisabeth | Carmen Sylva | Poête par la grace de Dieu, Reine par la volonté des homes’. The facsimile engraving on the base of her handwritten dedication increased the intimacy of the presentation and conveyed her sense of creative kinship with the artist.

In 1895, Lecomte du Nouÿ, favourite pupil of the painter Jean Léon Gérôme, visited Bucharest, where his brother André (1844-1914) was the Court architect of King Carol I. During a protracted sojourn he painted portraits of the royal family and decorated churches restored by his brother with frescos in neo-Byzantine style.

The firm of Telge held the Royal Warrant as silversmith and jeweller to the Roumanian court, a distinction most probably originating from its role in the restoration of the celebrated Pietroassa treasure prior to its exhibition in Paris at the Exposition Universelle of 1867. In this official capacity it supplied decorations and innumerable commemorative medallions, as well as bespoke work such as the present casket.

Bibliography:

Haydn Williams, Enamels of the World: 1700-2000 The Khalili Collections, London 2009, cat. 7, pp. 46–7.